Written by: Aydan Blackmon

Education, Community, and Resilience in Fort Mill

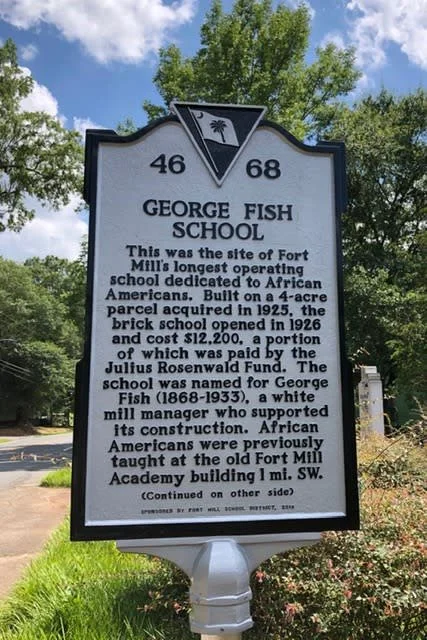

For more than four decades, the George Fish School stood as one of the most significant educational institutions for African Americans in Fort Mill, South Carolina. Located at what is now 401 Steele Street, the school opened in 1926 during the height of Jim Crow segregation, when Black students were denied access to white public schools. Historical records preserved by the Fort Mill History Museum, along with community archives such as the Archives of Amanda Castle (1917–2011), document the school’s lasting importance to generations of local families.

For many African American residents, George Fish School represented far more than access to education. It became a symbol of pride, resilience, and self determination within Fort Mill’s Black community.

Building Opportunity During Segregation

The school was originally established as the Fort Mill School after York County purchased four acres of land in 1925. Construction was made possible through a partnership between philanthropy and community investment.

Funding included support from the Rosenwald Fund, whose rural school building program expanded educational opportunities for African Americans throughout the South. Historical Rosenwald records show that $1,500 was contributed toward the total construction cost of $12,200, while the remaining funds were raised locally by the Black community and school district. This collaborative funding model reflected the broader educational vision promoted through initiatives connected to educator Booker T. Washington, whose work helped shape the Rosenwald school movement.

A School Designed for Learning

George Fish School followed the standardized six teacher Rosenwald floor plan, designed to maximize natural light, ventilation, and functional classroom space. The brick structure included six classrooms, a library, an auditorium with a stage, and a principal’s residence.

The decision to construct the building in brick distinguished it from many temporary wooden schools built for Black students during the era. According to local historical materials preserved by the Fort Mill History Museum and documentation prepared for the George Fish School Historical Marker Dedication by Fort Mill School District, George Fish, superintendent of Springs Mills Plants One and Two, advocated strongly for a more permanent structure. The school was later renamed in recognition of his support.

Leadership That Shaped a Community

Professor Elliott Littleton Avery served as the school’s first principal and became a deeply influential leader within Fort Mill’s Paradise community. His contributions are detailed in local research, including Cora Dunlap Lyles’ George Fish High School: Building a Dream, which highlights Avery’s role in establishing the school as both an academic institution and a center of civic life.

When Avery passed away in 1938, he was buried on the school grounds, an extraordinary tribute reflecting the respect he earned from students and families.

Expanding Access to Education

Initially serving grades one through eight, the school expanded its curriculum during the 1930s to include ninth grade. By 1941, it officially became George Fish High School. This transition marked a significant milestone at a time when secondary education opportunities for Black students in rural communities were limited.

State historical documentation, including the South Carolina Department of Archives and History African American Heritage Addendum (2019–2020), recognizes the school as the longest operating educational facility dedicated exclusively to African Americans in Fort Mill.

More Than a School

Beyond academics, George Fish School functioned as a cultural and social hub for the community. Events, performances, athletic programs, and gatherings strengthened community bonds and reinforced school pride.

Student life during the later years of segregation is preserved through The Dolphin yearbooks, produced between 1960 and 1967 and now available through Winthrop University Digital Commons. These publications offer valuable insight into student organizations, achievements, and everyday experiences during a period of national social change.

Additional historical interpretation, including community memories and monument research compiled by the Fort Mill History Museum and entries documented through HMdb.org’s George Fish School Marker Entry, further illuminate the school’s role in local life.

Desegregation and Transition

The school remained segregated until 1968. As court ordered desegregation and freedom of choice policies reshaped public education, enrollment declined. High school students transferred to Fort Mill High School, while elementary grades were reassigned to Riverview and Carothers schools.

According to materials prepared for the district’s historical marker dedication, the building was later repurposed as Fort Mill Junior High School for seventh and eighth grades, becoming the district’s first junior high facility. The elimination of African American only classes at George Fish marked the end of the dual school system in Fort Mill School District Four.

Remembering the Legacy

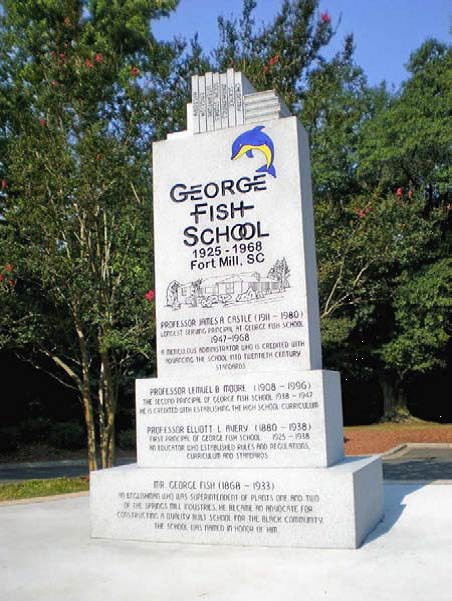

The building was sold in 1986 and later demolished, but its legacy continues through preservation efforts. In August 2007, the George Fish School Memorial Monument was unveiled near the original site, honoring the students, teachers, and families who shaped the institution. In 2019, the South Carolina Department of Archives and History installed an official historical marker recognizing the school’s significance and its connection to the Rosenwald School program.

Today, through archival collections, community scholarship, and ongoing interpretation by the Fort Mill History Museum, the story of George Fish School remains an essential part of Fort Mill’s history. Its legacy reminds us that education has long served as a foundation for resilience, opportunity, and community strength.

Pictured are the individuals who helped bring the George Fish School Monument to life. From left to right: Phillip Cargile, Jacky Harfield, Naomi Stanley, John Sanders III, Ruth Meacham, Rufus Sanders, Elizabeth Patterson White, and Osby Watts.

Want to learn more about the George Fish School?